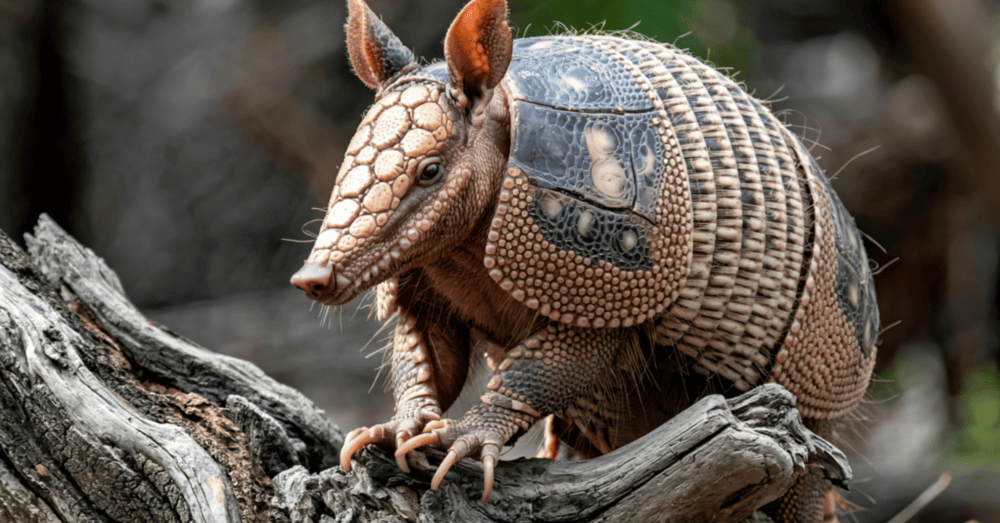

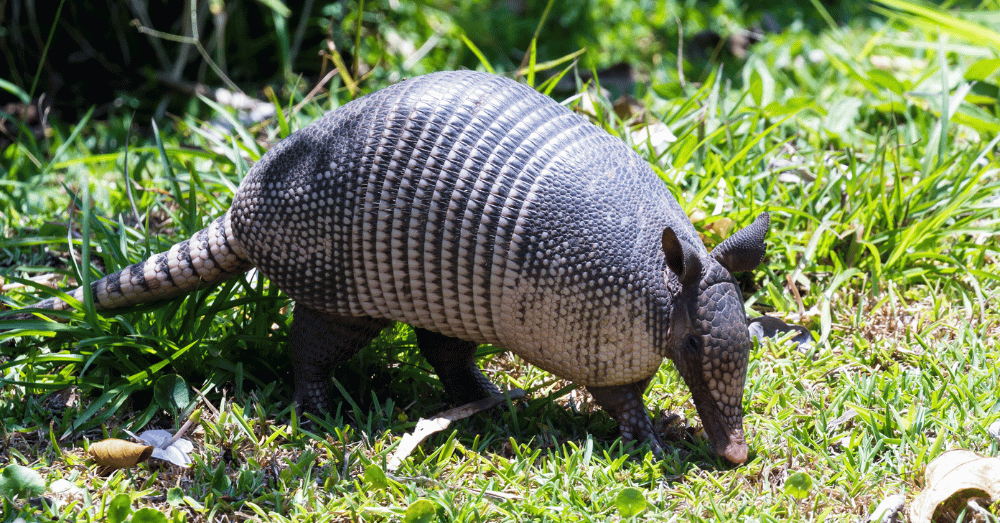

Drive through southern Indiana these days and you might spot something that would’ve seemed impossible two decades ago: a house-cat-sized creature with a bony shell waddling across your lawn or lying squashed on the highway. Welcome to armadillo country. Indiana has officially joined the club of states hosting breeding populations of nine-banded armadillos, and this southern transplant is shaking things up in ways nobody expected.

- Indiana became the 17th state with an established armadillo population, with over 230 confirmed sightings since the early 2000s and nearly 90% of reports coming after 2017.

- Climate change and milder winters have allowed armadillos to survive in Indiana year-round, spreading along river corridors like the Wabash and White rivers from Illinois.

- The animals are causing increased roadkill, torn-up lawns, and competition with native species like moles and shrews, though leprosy transmission remains a low risk for decades to come.

When Did These Shell-Backed Invaders Show Up?

The first confirmed armadillo sighting in Indiana happened in Gibson County back in 2003. Back then, it was treated like a novelty. Fast forward to 2025, and wildlife biologists have confirmed more than 230 sightings across the state. What changed? The answer lies in warming temperatures and the armadillo’s surprising adaptability.

Brad Westrich, state mammologist for the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, puts it plainly. Armadillos have been creeping northward as winters get milder, opening up habitats that were previously too cold for survival. These animals lack the insulating fat needed to handle extended freezing temperatures, and they can’t hibernate. When the ground freezes solid, they’re stuck in their burrows, often facing starvation or freezing to death.

Mild winters mean survival. The armadillos likely migrated from southeastern Illinois, using the state’s river systems as natural highways. The Ohio River acts as a barrier preventing migration from Kentucky, so most of Indiana’s armadillos are Illinois transplants following waterways like the Wabash and White rivers.

Where Are the Armadillos Spreading?

Armadillo reports cluster heavily in southwestern Indiana, but they’re pushing boundaries fast. Sightings have been confirmed as far north as Porter County, less than five miles from the Michigan state line. They’ve been spotted near Greenwood, Indiana, in Johnson County, and as far east as the Flatrock River in east-central Indiana, putting them less than 60 miles from the Ohio border.

Armadillos love forested areas near water. Rivers, lakes, ponds, and even roadside ditches create perfect hunting grounds because insects thrive in those environments. Highways mimic these riverside habitats, which explains why so many armadillo sightings involve roadkill. Bridges over rivers that armadillos couldn’t normally cross have become convenient migration corridors.

The Roadkill Problem Gets Real

Armadillos have earned themselves a grim nickname in neighboring states. Their roadkill numbers are staggering. When startled, armadillos instinctively jump three to four feet straight up in the air. This reflex might work against ground predators, but it’s deadly when facing cars. They’re small enough to pass under vehicles unharmed, but that jump puts them directly into collision with the undercarriage.

Most armadillo reports in Indiana come from daytime observations of roadkill on state highways. These are primarily nocturnal animals, emerging around sunset to forage through the night. As temperatures drop in fall and winter, they shift to daytime activity to avoid the cold.

What Do Armadillos Mean for Indiana’s Ecosystem?

Wildlife biologists are still studying the full impact armadillos will have on Indiana’s ecosystems. Right now, the animals are in what researchers call a “honeymoon period.” With few natural predators like coyotes and bobcats posing much threat, armadillos can expand their numbers quickly.

The biggest concern involves competition for food. Armadillos are insectivores, feeding mainly on beetles, ants, and other invertebrates. This puts them in direct competition with native species like shrews, moles, skunks, and opossums. Whether armadillos will outcompete these smaller insectivores remains to be seen.

There’s a potential upside, though. Armadillos are powerful diggers, excavating extensive burrow systems with multiple tunnels and chambers. These abandoned burrows become homes for rodents, reptiles, amphibians, and even birds. Scientists sometimes call armadillos “ecosystem engineers” because their digging behavior moves soil, contributes to nutrient cycling, disturbs plants and seeds, and creates habitat for other species.

Backyard Battles and Property Damage

Homeowners are discovering the downside of armadillo neighbors. These animals have incredibly strong, sharp claws built for digging. They tear up lawns and gardens while rooting for insects, leaving behind holes and uprooted plants. Their burrow systems can extend under sheds, barns, and foundations, creating structural concerns for property owners.

Indiana law protects armadillos from trapping or killing unless they’re causing substantial property damage. If damage occurs, landowners can remove the animals without a permit or hire a licensed wildlife control operator. Otherwise, residents are encouraged to report sightings to the DNR through their “Report a Mammal” webpage.

The Leprosy Question Nobody Wants to Ignore

Armadillos are the only known non-human mammals that can contract and carry leprosy, caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae. In states like Florida, Louisiana, and Texas where armadillo populations have existed for decades, leprosy cases among humans have doubled since 2013. Should Hoosiers worry?

Not yet. Westrich explains that leprosy is a “density-dependent pathogen” requiring large armadillo populations to pose a real risk. Indiana sits on the leading edge of armadillo expansion, meaning population densities remain low. In Illinois, recent studies testing armadillos for leprosy came back negative despite growing populations.

Experts estimate it could be decades before leprosy becomes a concern in Indiana. Transmission occurs when humans handle contaminated soil where infected armadillos have burrowed and defecated, or when people eat armadillo meat. The CDC notes that over 95% of the global human population has natural immunity to leprosy, and the disease is completely curable with antibiotics.

Living with Indiana’s Newest Resident

Armadillos aren’t going anywhere. With mild winters continuing and few natural predators, their numbers will likely keep growing. Wildlife experts predict the species will eventually reach Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Connecticut before their expansion is limited by harsh winters they simply can’t survive.

For now, Hoosiers are learning to coexist. If you spot an armadillo, give it space. These animals have terrible eyesight but excellent hearing and sense of smell. They might bumble right past you without noticing until you move. Take photos, report sightings to the DNR, and resist the urge to corner or handle them.

As populations grow, people will probably become less thrilled about their new neighbors. But for now, armadillos remain a curiosity. These armored invaders represent a real-time example of how climate change reshapes ecosystems, pushing species into territories that were inhospitable decades ago.

Looking Ahead: Armadillos are Here to Stay

Indiana’s armadillo story is still being written. Biologists continue tracking population growth, monitoring ecosystem impacts, and studying how native wildlife adapts to this new competitor. The data collected from public sightings helps researchers understand distribution patterns and movement behaviors.

Will armadillos become as common as raccoons and opossums? That depends on winter severity and how well the species adapts to Indiana’s unpredictable weather. One brutal winter with extended below-freezing temperatures could knock populations back significantly. But if mild winters persist, expect to see more of these tank-like creatures waddling through backyards, digging up lawns, and unfortunately, meeting their end on Indiana highways.

One thing’s certain: Indiana’s wildlife landscape is changing, and armadillos are here to stay, at least for now. Whether they become a beloved quirk of Hoosier wildlife or a persistent nuisance depends on how their populations grow and how communities learn to live alongside them.

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning we may earn a commission if you make a purchase. There is no extra cost to you. We only promote products we believe in.